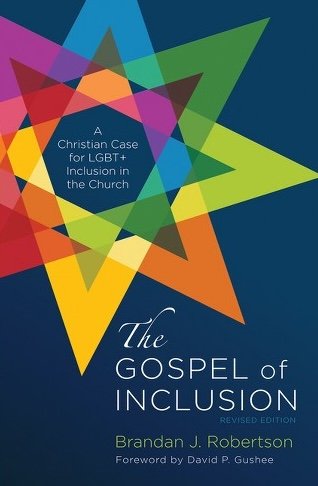

What does the Bible say about

queer people?

Reclaiming the Bible for Love

I've come to realize that a thorough examination of the Bible, considering its culture, context, and language, can dramatically change many of the "obvious" interpretations commonly held. The accessibility of the Bible, a result of the Protestant Reformation and the printing press, has been both a blessing and a curse. It democratized Christianity and removed power from church leaders who could manipulate the Bible for their own gain. However, it also led to billions having access to a complex ancient text, with many lacking the means or interest to study its origins, resulting in numerous inaccurate and often harmful interpretations.

As Christians, we should emulate the Bereans from Acts 17:11, who examined the Scriptures carefully with the best scholarship available before forming doctrines. While the Bible contains problematic sections reflective of its Bronze-Age origins, throughout centuries, guided by the Holy Spirit, people have moved beyond some of its directives to adopt more ethical ways of living. For instance, the Bible doesn't explicitly condemn slavery, yet most modern Christians rightly oppose it.

There's considerable debate in Biblical scholarship about certain passages, and you'll find differing opinions on the interpretations I've presented. This is what makes Biblical scholarship both intriguing and exhausting. Ultimately, interpreting the Bible involves a choice, guided by scholarship and our understanding of ethics and morals.

The ethical paradigm I adhere to comes from Jesus, who summarized the entire Hebrew Bible with two commands: love God and love your neighbor. This ethic of love should guide our interpretation of Scripture.When considering queer people, their lives, and love, I am convinced that no clear condemnation exists in the Bible. The lack of harm caused by queer love, coupled with the flourishing it brings when individuals live authentically, leads me to reject the notion that queerness is sinful.

I'm concerned when Christians cling to anti-queer rhetoric, as it often stems not from Biblical conviction but deeper personal discomforts. We should encourage reflection on these feelings rather than rely on misinterpretations of Scripture.

The Bible is a library of texts, a compilation over thousands of years, reflecting people's struggles, beliefs, and morals. When engaged with critically, respectfully, and through the lens of love, it connects us to God and each other. But misused, it can justify prejudices and cause harm. Thus, we must approach the Bible with care, ready to wrestle with its words and committed to the most loving interpretations possible.

What follows is a summary of what I understand to be the best historical and Biblical arguments against the anti-queer usage of the clobber passages. I hope these short summaries can help you as you begin your own journey of reconciling your Christian faith and queer identity.

Rev. Brandan Robertson

-

Ancient creation stories, such as those found in Genesis, are often misinterpreted when taken literally, especially concerning gender roles and relationships. These narratives were crafted in a vastly different historical and cultural context, primarily to establish a sense of identity and cultural norms for a specific group of people. Their primary aim wasn't to provide a factual account of human origins or to set universal standards for relationships and gender identities.

In many creation myths, the portrayal of gender and relationships reflects the societal norms and survival needs of the times. The emphasis on heterosexual relationships, for instance, was largely driven by the imperative of procreation, crucial for the survival and continuation of a community. This historical context suggests that the stories were more about the survival and ordering of society rather than moral judgments on the nature of relationships.

Furthermore, the recognition of a spectrum of gender identities in ancient religious and cultural texts indicates a more nuanced understanding of gender than a strict binary. This perspective challenges the contemporary literal interpretation of these texts to justify rigid gender roles or exclusively heterosexual norms.

We must understand Genesis 1-2 as symbolic narratives that convey universal themes like the value of human relationships and the dignity of all individuals, rather than as prescriptive texts dictating specific models of gender identity and relationships. This approach allows for a more inclusive understanding that respects the diversity and complexity of human experiences.

-

The story of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19, often cited as a condemnation of homosexuality, is actually focused on xenophobia and the abuse of power. In this narrative, two angels visit Lot in the notoriously immoral city of Sodom. Lot, aware of the danger posed by the townspeople, urges the angels to stay with him for safety. However, men from all over Sodom surround Lot's house, demanding to sexually assault the visitors. This demand is a display of dominance and aggression rather than a manifestation of homosexual desire, reflecting a common practice in ancient patriarchal societies where sexual violence was used to assert power and emasculate others.

The real sin of Sodom, as described in the Book of Ezekiel 16:49, is not homosexuality but arrogance, overindulgence, and neglect of the needy. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that the men of Sodom were seeking to harm angelic beings, considered extensions of the divine in Jewish tradition. The New Testament also references the men of Sodom lusting after “strange flesh” (Jude 1:7), likely alluding to the non-human nature of the angels rather than a same-sex attraction.

This perspective is corroborated by historical interpretations of the sins of Sodom, which originally referred to a range of non-procreative sexual acts, not exclusively homosexual relationships. The specific association of Sodom with homosexuality emerged much later, particularly with the writings of the Catholic Reformer Peter Damien in the 11th century, who used the term "sodomia" in a broader context of moral decay in the Church, but it later became narrowly interpreted as referring only to same-sex relations. This association was more a product of later theological developments than a reflection of the original narrative or its earliest interpretations.

-

The Book of Leviticus, an ancient law book for the Hebrew people, contains passages often cited in discussions about same-sex sexual behavior. It's crucial to understand that Leviticus was written by and for the Hebrew people, to preserve their distinct cultural and religious identity. This context is essential for interpreting its laws, especially those regarding same-sex intercourse, as they were not intended as a universal moral code but were specific to the Hebrews' ritual and cultural practices.

In Leviticus, there are two notable passages (18:22 and 20:13) that address same-sex relations between men. These are part of the Holiness Code, aimed at differentiating the Israelites from the Egyptians and Canaanites, among whom they lived. The prohibitions were not about morality per se but about maintaining ritual purity and distinctiveness. The term "abomination" used in these texts (to'eva in Hebrew) refers more to cultural or religious taboo than to an ethical wrong.

Leviticus 18:22 prohibits a man from lying with another man as with a woman, labeling it an abomination. This prohibition, however, must be seen in the context of the entire chapter, which is about avoiding the practices of the Egyptians and Canaanites. The exact nature of the same-sex relationships referred to is not explicitly clear. Some scholars suggest it could relate to practices like sacred prostitution or same-sex incest, while others think it may target exploitative relationships, such as those between a man and his male slave.

Leviticus 20:13 repeats this prohibition, adding the death penalty for such acts. This harsh penalty reflects the text's emphasis on survival and maintaining social order, crucial for the small, struggling Israelite community. It's important to note that most transgressions listed in Leviticus 20, not just same-sex relations, were deemed punishable by death, indicating the severity with which the community sought to uphold its cultural and ritual purity.

In summary, Leviticus' prohibitions on same-sex relations were context-specific, aimed at preserving the distinct identity and survival of the Hebrew people. They were not meant as universal moral dictates. Modern interpretations that use these passages to condemn LGBTQIA+ relationships overlook the cultural, historical, and authorial context of Leviticus. Such interpretations are inconsistent, as they often ignore other aspects of the Holiness Code, like dietary laws or fabric restrictions, while focusing selectively on the passages about same-sex relations.

-

Deuteronomy 22:5, often cited in contemporary debates about gender expression and drag performances, must be understood in its historical and cultural context. This verse, stating that a woman must not wear men's clothing and vice versa, is part of the Deuteronomic Code, a set of laws intended to preserve the distinct identity and religious practices of the Hebrew people.

The Deuteronomic Code, found in Deuteronomy chapters 12 to 26, was established to guide the Hebrews in the Promised Land and to purify their culture from pagan influences absorbed from the Canaanites. This context is crucial for understanding Deuteronomy 22:5. The prohibition against cross-dressing in this verse was likely aimed at preventing participation in Canaanite religious practices, which may have included ceremonial cross-dressing in rituals honoring deities like Astarte.

The historical evidence suggests that everyday clothing for Hebrew men and women was quite similar, implying that the verse's focus was more on special occasions or rituals, rather than everyday dress. The law's primary concern was with actions that could be construed as worship of other gods, not with general clothing choices or gender expression.

In a broader sense, Deuteronomy, like Leviticus, was not a universal moral code but a specific set of laws for a specific people in a specific time and place. The laws were designed to maintain the Hebrews' cultural and religious distinctiveness and are not directly applicable to non-Jewish or contemporary contexts.

Thus, using Deuteronomy 22:5 to condemn modern practices like drag performances or to judge transgender and gender non-conforming individuals is a misapplication of the text.

Gender expression varies widely across cultures and historical periods, and what is considered appropriate for one gender in one era or culture can be very different in another. The passage in Deuteronomy reflects the cultural and religious concerns of its time and does not provide a basis for making ethical judgments about gender expression in the modern world.

In summary, Deuteronomy 22:5's prohibition against cross-dressing was contextually tied to specific religious practices and concerns of the ancient Hebrews and does not serve as a relevant or appropriate reference for contemporary discussions on gender identity and expression.

-

In Matthew 19:1-12, Jesus addresses a question about divorce, not about queer relationships or gender identity. The Pharisees question Jesus on the lawfulness of divorce, to which Jesus responds by referencing the Creation account in Genesis, emphasizing the enduring commitment of marriage. His answer focuses on the permanence of the marital bond, as understood in his cultural and religious context, rather than offering a comprehensive doctrine on all possible forms of marriage.

This passage is sometimes interpreted by traditionalists as evidence that Jesus viewed marriage as exclusively between a man and a woman. However, this interpretation overlooks the specific context of the question Jesus was answering. He was addressing a query about divorce in a heterosexual marriage, using language and concepts relevant to that specific scenario. This does not equate to a broader statement on the legitimacy of queer marriages, as the passage simply doesn't address this topic.

Furthermore, Jesus' discussion about eunuchs in the same passage suggests an awareness and acceptance of people who did not conform to traditional gender and sexual norms of the time. Eunuchs, who could be intersex, castrated, or otherwise gender non-conforming, were recognized by Jesus as valid and integral members of society, even if they didn’t fit into the typical marital structures.

Jesus’ teachings, as recorded in the Gospels, show no explicit condemnation of queer people or relationships. His response to the question about divorce highlights the importance of commitment and fidelity within a marriage context, rather than setting a prescriptive norm for all marriages. To use this passage to argue against queer relationships or marriages is to misinterpret Jesus' words and to impose a contemporary issue onto a text that was addressing a different question in its own historical and cultural setting.

-

In Romans 1:18-32, the Apostle Paul appears to condemn same-sex sexual activities, but a deeper look into the context reveals a different interpretation. Paul, a Hellenistic Jew and Roman citizen, was often reacting against the Greco-Roman world's philosophy and culture, particularly its hedonism and idolatry. His writings show the influence of Stoicism, which viewed sexual desire skeptically.

Paul describes the decline of Roman society into godlessness and idolatry, linking this moral decay to sexual immorality, specifically the sexual excesses common in Roman pagan worship, such as orgies. He argues that abandoning worship of the true God leads to a degradation of moral values, manifesting in idol worship and various forms of sexual excess, including same-sex activities.

In this context, Paul's criticism of same-sex behaviors in Romans 1:26-27 is closely tied to idolatry. He views these behaviors as a consequence of Roman society's idol worship, not as an inherent moral failing of the individuals. The focus is on the uncontrollable lust and societal decadence resulting from idolatry, not on a condemnation of loving, consensual same-sex relationships.

Paul's reference to women exchanging natural sexual relations for unnatural ones, and men committing shameful acts with other men, likely refers to practices common in Roman society, such as pederasty and the sexual use of slaves. These practices were exploitative and reflective of societal power imbalances, not of mutual, loving relationships.

The cultural context of the Greco-Roman world must be considered. Sex was often tied to social status rather than romantic desire, with Roman men freely exploiting their slaves. Roman society's patriarchal norms allowed men to sexually abuse slaves of both genders without jeopardizing their status. Similarly, Roman women's close relationships with their female slaves might have involved sexual abuse, which Paul condemns.

Paul's words in Romans 1 should not be universalized. He was addressing the specific cultural and moral context of first-century Rome, marked by idolatry, sexual exploitation, and a lack of self-control, rather than making a statement about all same-sex relationships.

In conclusion, Romans 1 is not a blanket condemnation of modern, loving, same-sex relationships. Instead, it criticizes the idolatrous and exploitative sexual practices of Roman society. To interpret this passage as a direct condemnation of consensual same-sex relationships is to misunderstand Paul's intent and the cultural context of his writing.

-

In 1 Corinthians 6, the Apostle Paul addresses various moral concerns within the Corinthian church. Amidst these issues, he includes a list of vices, commonly known as a "vice list," which was a typical rhetorical device in ancient teachings. This list includes various wrongdoings, including sexual immorality, idolatry, theft, greed, and drunkenness.

The controversy arises with Paul's use of two Greek terms, mαλακοὶ (malakoi) and ἀρσενοκοῖται (arsenokoitai), often interpreted as referring to homosexual behavior. However, understanding these terms requires examining the cultural and historical context of Corinth and the broader Greco-Roman world.

Malakoi, literally meaning "soft," commonly referred to effeminate male prostitutes in the Greco-Roman world. It was also used to describe those considered morally weak or lacking self-control. In the patriarchal society of that time, certain men, such as slaves, prostitutes, or young men, were socially permitted to be sexually penetrated as it was seen as an assertion of dominance by the penetrating party, reflecting the societal hierarchy.

Arsenokoitai, a term Paul seemingly coined, has been a subject of much debate regarding its precise meaning. It appears to be a compound word derived from "arsen" (man) and "koite" (bed), and is thought to be linked to the prohibitions in Leviticus, which in the Greek translation used these words in the context of prohibitions against certain sexual practices. This term likely referred to men who engaged in exploitative sexual relationships, such as with male prostitutes or slaves, rather than consensual same-sex relationships.

Paul's criticism of these behaviors appears to be more about the exploitative and idolatrous nature of the sexual acts common in Corinth, particularly those associated with temple prostitution and the abuse of social inferiors. This interpretation is supported by the broader context of 1 Corinthians, where Paul discusses issues related to sexual immorality and idolatry, including prostitution.

Importantly, the concept of sexual orientation as understood today did not exist in the first century. The Greco-Roman world did not categorize people based on the gender of their sexual partners. Thus, translating arsenokoitai as "homosexuals" is anachronistic and misleading. The term likely referred to specific exploitative sexual practices rather than a blanket condemnation of all same-sex relationships.

In summary, the terms malakoi and arsenokoitai in 1 Corinthians 6 are best understood as references to specific forms of exploitative and idolatrous sexual behavior prevalent in the Greco-Roman culture of the time. Their use by Paul does not constitute a general condemnation of consensual same-sex relationships as understood in contemporary society.

-

In Paul's letter to Timothy, found in 1 Timothy 1:8-10, he again lists various vices, including the use of the term "arsenokoitais." This letter, like his others, is set against the backdrop of the Greco-Roman world, with its own unique cultural and religious practices. Paul’s focus on certain behaviors, particularly those related to sexual ethics, reflects the prevailing issues in these early Christian communities.

The context of this letter is Paul's discussion about the proper use of the law, as outlined in the Hebrew Bible. He categorizes various behaviors as contrary to "sound teaching" and the gospel. Among these, he includes "porneia" (often translated as sexual immorality or deviancy), "arsenokoitais" (a term Paul coined), and "andrapodistais" (slave traders or enslavers).

Paul's use of "arsenokoitais" in this passage, similar to its use in 1 Corinthians, likely refers to exploitative sexual practices. The grouping of "arsenokoitais" with "porneia" and "andrapodistais" suggests a link to sexual exploitation, possibly in the context of slavery or prostitution. This interpretation is reinforced by the historical context of Ephesus, a city known for its worship of Artemis and the associated licentious practices, which may have included various forms of prostitution.

The term "arsenokoitais," as argued previously, does not equate to the modern concept of homosexuality. Instead, it appears to refer to specific exploitative sexual behaviors prevalent in the Roman Empire, where prostitution and the sexual use of slaves were widespread. The fact that Paul does not use any of the available Greek terms that directly referred to same-sex relationships or activities further supports the argument that "arsenokoitais" targeted a specific practice, not all same-sex relationships.

Paul's inclusion of "arsenokoitais" in a vice list alongside sins like murder, enslavement, and lying should not be interpreted as an outright condemnation of all homosexual relationships. Instead, it reflects his concern with the cultural and religious practices of the time, particularly those involving sexual exploitation and idolatry.

In summary, the best understanding of "arsenokoitais" in Paul's letter to Timothy is a reference to specific forms of sexual exploitation linked to the cultural and religious context of the Greco-Roman world, rather than a blanket condemnation of consensual same-sex relationships.

-

The Book of Jude, a short letter in the New Testament, includes a passage referencing the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah from Genesis 19. Jude uses this reference in a broader argument against certain behaviors and beliefs that he saw as corrupting the early Christian community. This letter has been interpreted in various ways, but a common anti-queer reading of Jude's reference to Sodom and Gomorrah is that it condemns homosexual behavior. However, this interpretation overlooks the actual context of both the original story in Genesis and Jude’s specific use of it.

Jude mentions Sodom and Gomorrah as examples of indulgence in sexual immorality and pursuit of unnatural lust, which led to their destruction. The traditional anti-queer interpretation focuses on the aspect of sexual immorality, often equating it with homosexual acts. However, as previously discussed in the context of Genesis 19, the sin of Sodom and Gomorrah was not homosexuality per se but rather their extreme violation of hospitality norms and xenophobia, manifesting in the attempted gang-rape of angelic visitors.

The key point in Jude's reference is the "unnatural lust" towards angelic beings, not human same-sex relationships. The men of Sodom and Gomorrah did not know these visitors were angels, but their intent to dominate and abuse strangers reflects their moral corruption, not a commentary on consensual same-sex relationships.

Furthermore, Jude's letter is concerned with false teachings and immoral behaviors that deviate from early Christian teachings, using the story of Sodom and Gomorrah as a metaphor for divine judgment against such transgressions. The focus is on the broader theme of rebellion against God, rather than a specific condemnation of homosexuality.

In conclusion, Jude's reference to Sodom and Gomorrah is not a direct condemnation of queer people or consensual same-sex relationships. Instead, it is a part of his argument against certain behaviors and beliefs that he saw as contrary to Christian teachings. The story of Sodom and Gomorrah, in both Genesis and Jude, centers on issues of hospitality, violence, and disrespect for the divine, rather than being a commentary on the morality of homosexual acts.